The Ancient Seeds of Evil

Let’s explore the Devil’s complex story together in two parts. Our story begins not with the Christian Devil we recognize today, but in the dusty scrolls of ancient Hebrew literature, where we first encounter "ha-Satan" literally meaning "the adversary". This early figure wasn't the ultimate enemy of God we might expect, but something more like heaven's prosecuting attorney. In the Book of Job, we see Satan appearing before God's throne, not as a rebel, but as a member of the divine court whose role is to test human faith and bring accusations.

But here's where the tale takes a dramatic turn. When the Jewish people returned from Babylonian exile around 550 BCE, they brought back more than memories and traditions, they carried revolutionary theological ideas influenced by Persian Zoroastrianism. This dualistic religion, with its cosmic battle between Ahura Mazda (light/good) and Angra Mainyu (darkness/evil), fundamentally transformed how evil was understood in Jewish thought. Suddenly, Satan evolved from a heavenly functionary into something far more sinister, a genuine opponent of the divine order.

The transformation wasn't immediate or complete. Early medieval theologians struggled with this evolution, creating what we might call a "theological biography" of Satan. Augustine of Hippo provided one of the most influential frameworks: evil wasn't something God created, but rather the absence of good, like darkness being the absence of light. Satan, in this view, became evil through his own free will, choosing pride over obedience, a theological concept that would exist through centuries of art and literature.

Meanwhile, in the Greek world, evil operated on entirely different principles. The Greeks had their kakodaimones, malevolent spirits that influenced humans toward wicked acts, but these existed alongside benevolent daimones in a complex spiritual ecosystem. Evil wasn't centralized in one supreme figure; it was distributed across various entities and abstract personifications like Eris (discord), Apate (deceit), and the fearsome Furies. Even Hades, ruler of the underworld, wasn't evil in the way we understand Satan, he was stern, feared, and inflexible, but not malevolent or actively working against divine order.

The Medieval Imagination Takes Shape

The visual story of the Devil begins in the 6th century with what may be the earliest artistic representation of Satan in Western art. In the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, a remarkable Byzantine mosaic depicts the parable of the sheep and goats from Matthew's Gospel. Here, Christ sits in judgment, flanked by two angels. To his right stands a red angel representing divine mercy, while to his left appears a blue angel, and this blue figure, according to art historians like Jeffrey Burton Russell, is actually Lucifer himself.

This early Satan is clear in his restraint. He wears a halo and appears dignified, almost beautiful, there are no horns, no grotesque features, no obvious markers of evil. The blue color wasn't arbitrary; in 6th-century Christian symbolism, blue represented the dense, heavy air below the heavens. This Satan still retained his angelic nature, a fallen star rather than the monstrous beast he would later become.

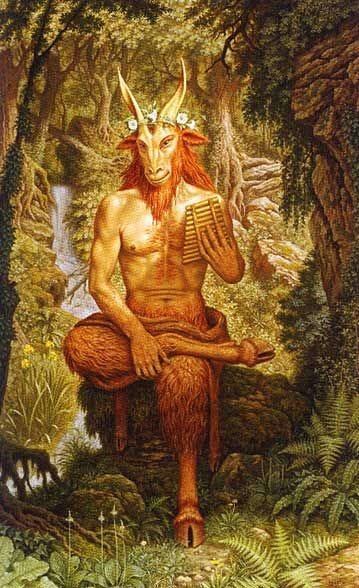

The transformation accelerated during the medieval period as Christian theology merged with European pagan traditions. Teutonic gods were often reinterpreted as demons, and nature spirits like dwarfs and elves became seen as diabolic entities. The visual representation of Satan began borrowing heavily from pagan imagery, particularly the Greek god Pan with his goat horns, hooves, and overall bestial appearance. By the 11th century, this fusion was complete, Satan had acquired his now-familiar horns, tail, and cloven hooves, an image that would dominate Western art for centuries.

Medieval manuscripts provide a fascinating glimpse into how these evolving ideas about Satan were visualized. The famous Codex Gigas, also known as the "Devil's Bible," contains what some historians claim is the first full-page portrait of Satan in manuscript form. Created in early 13th-century Bohemia, this massive manuscript (weighing 75 kilograms) includes a striking image of Satan as a large, greenish figure with horns, claws, and a lolling tongue. Legend claimed the entire manuscript was created by a monk who made a deal with the Devil himself, when faced with an impossible task, he supposedly asked Satan for help, and the Devil agreed in exchange for his portrait being included in the sacred text.

The Great Artists Envision Hell

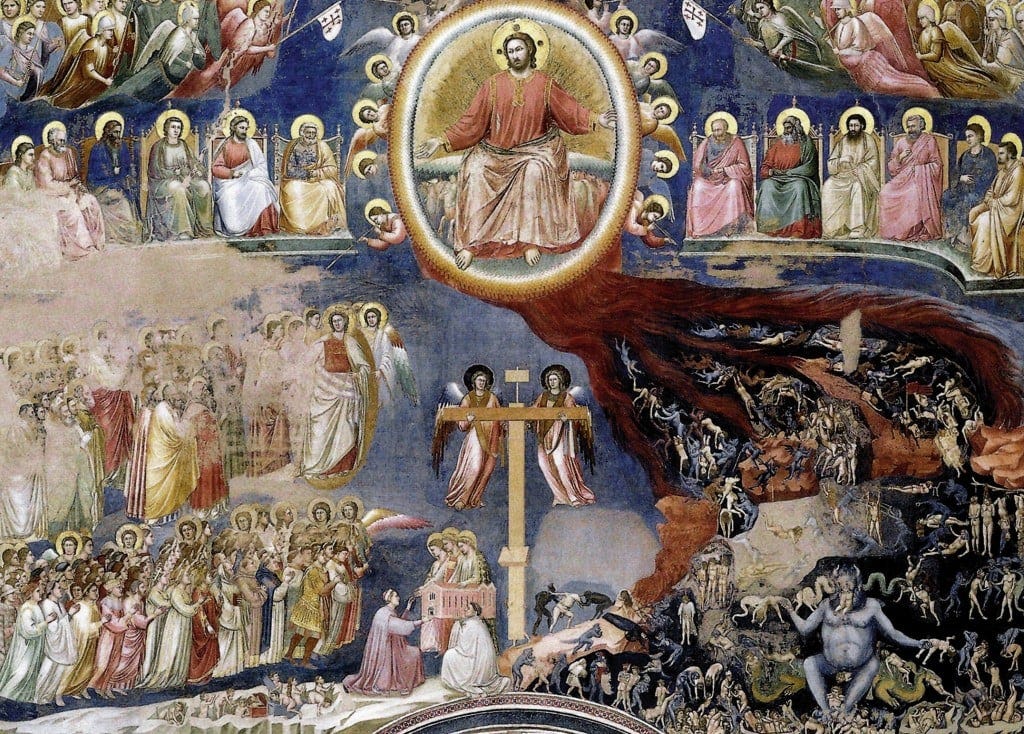

The late medieval period saw an explosion of diabolic imagery as artists began creating some of history's most memorable depictions of Satan and Hell. Giotto's "Last Judgment" in the Scrovegni Chapel (c. 1307) presents one of art's most dramatic hellscapes. In the lower right corner of this monumental fresco, a gluttonous, horned monster, unmistakably Satan, sits at the gates of Hell, devouring sinners before excreting them in an endless cycle of consumption and degradation. This Satan isn't subtle or philosophical; he's a pure eating machine, all about gluttony and the mechanical horror of eternal punishment.

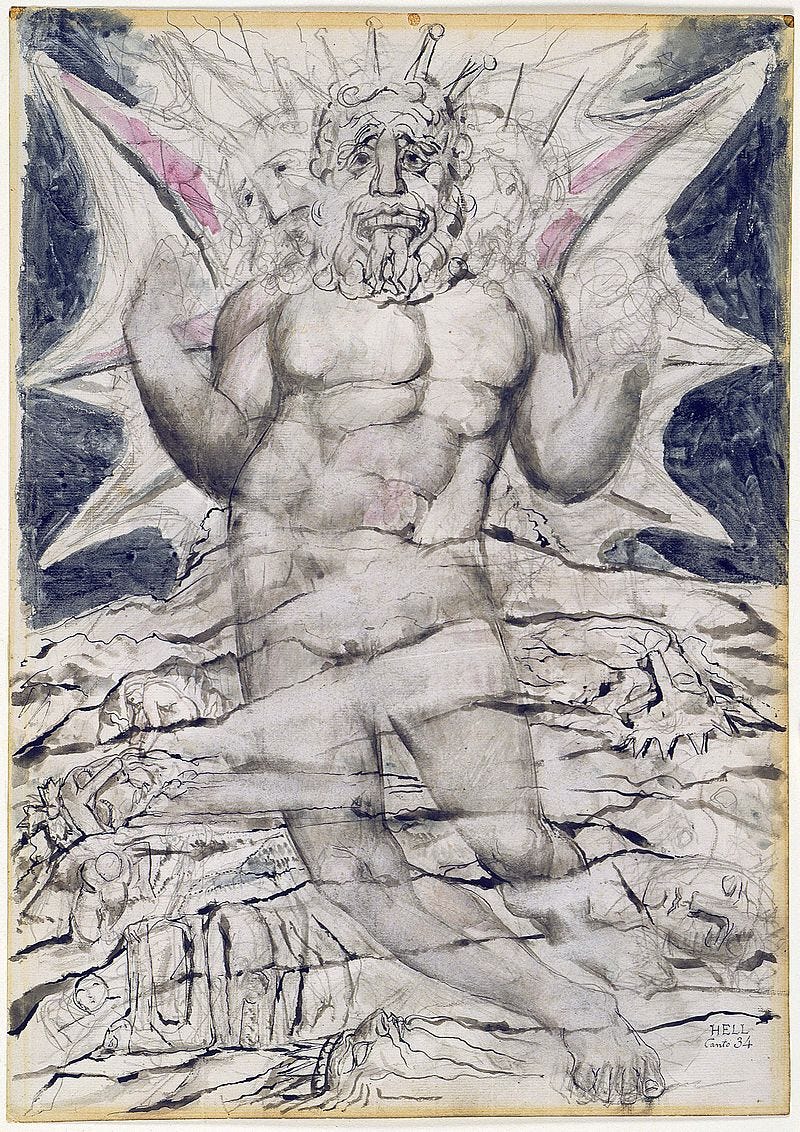

Giotto's contemporary Dante Alighieri had just begun writing his "Divine Comedy," and the two men likely knew each other, historian Giorgio Vasari describes them as "dear friends". This connection becomes crucial because Dante's literary vision would profoundly influence how artists depicted Satan for centuries to come. In the final cantos of the "Inferno," Dante presents Satan as a three-headed giant frozen in ice at the center of Hell, mindlessly chewing on history's greatest traitors: Judas Iscariot, Brutus, and Cassius. This Satan is paradoxical, simultaneously the most evil being in creation and yet pathetically powerless, his own wing-beats freezing him deeper into his icy prison.

Fra Angelico's "Last Judgment" (c. 1431) offers another masterpiece of diabolic imagination. In the hell section of this tempera painting, now housed in Florence's Museo di San Marco, a massive black demon dominates the lower right corner, devouring the damned while smaller demons torture souls with medieval efficiency. Fra Angelico, despite being known as the "Angelic Painter," created some of the most viscerally disturbing hellscapes in art history. His demons work with craftsman-like dedication, using flesh hooks, cauldrons, and various torture implements more like contemporary kitchen and workshop tools.

But it was Hieronymus Bosch who truly revolutionized how we visualize Hell and its inhabitants. His masterwork, "The Garden of Earthly Delights" (c. 1490-1500), presents a hell that's both more inventive and more psychologically penetrating than anything created before. The right panel of this triptych, often called the "Musical Hell," shows demons using musical instruments as torture devices, creating a cacophony of eternal suffering.

In Bosch's hell, a bird-headed creature with an enormous eye, possibly Satan himself, sits on a throne that's simultaneously a toilet, devouring naked humans and immediately excreting them into a pit below. Nearby, demons work with industrial efficiency: some operate giant musical instruments with human bodies stretched across them like strings, others tend to furnaces where souls are processed like raw materials. This isn't the theological hell of medieval treatises; it's a working hell, a factory of suffering that reflects the emerging commercial world of the Netherlands.

The journey isn't over yet! Join me for the concluding part, where the story continues with Renaissance artistry, the Romantic spirit, modern interpretations, and the Devil’s visual legacy through the ages