Salome's Burden

When a Biblical Dancer Becomes a Mirror

The story of Salome begins in the Gospels of Mark and Matthew, where she appears as an unnamed dancer who requests the head of John the Baptist on a platter. This sparse biblical account gives us a little psychological detail, yet it contains all the elements that would captivate artists for centuries: a young woman, a seductive dance, a gruesome demand, and the death of a holy man. Early Christian writers quickly filled in the gaps, reshaping this brief episode into a cautionary tale about female sexuality and moral corruption. By the time medieval theologians finished with her story, Salome had become a symbol of dangerous femininity, her dance representing the perils of bodily desire and her request for John’s head proof of woman’s capacity for cruelty.

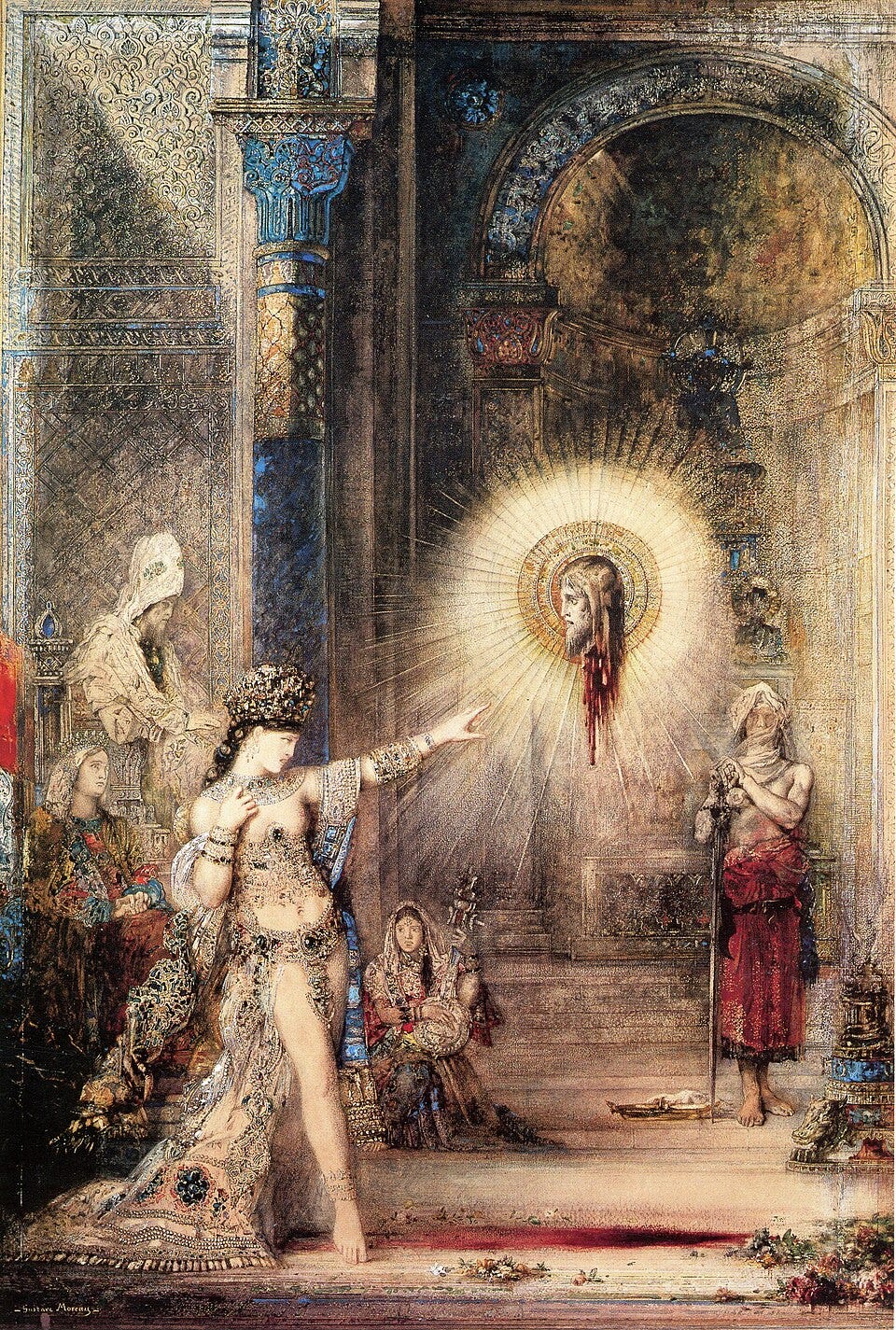

The Dance of the Seven Veils, though never mentioned in biblical texts, became the centerpiece of Salome’s story through centuries of artistic and literary embellishment. Oscar Wilde’s 1891 play cemented this addition into popular imagination, but artists had long understood that the dance was where Salome’s psychological complexity truly lived. In their paintings and sculptures, the dance becomes a site of the deepest enigma: Is she a willing seductress or a manipulated child? Does she dance with malicious intent or innocent ignorance of the consequences? Gustave Moreau’s obsessive series of Salome paintings clearly show this tension perfectly, highlighting her suspended in jeweled, dreamlike spaces where she appears both powerful and trapped. The dance allowed artists to explore the uncomfortable territory between victimhood and agency, to show a woman wielding sexual power while simultaneously being wielded by male desire and male authority figures who orchestrate her performance.

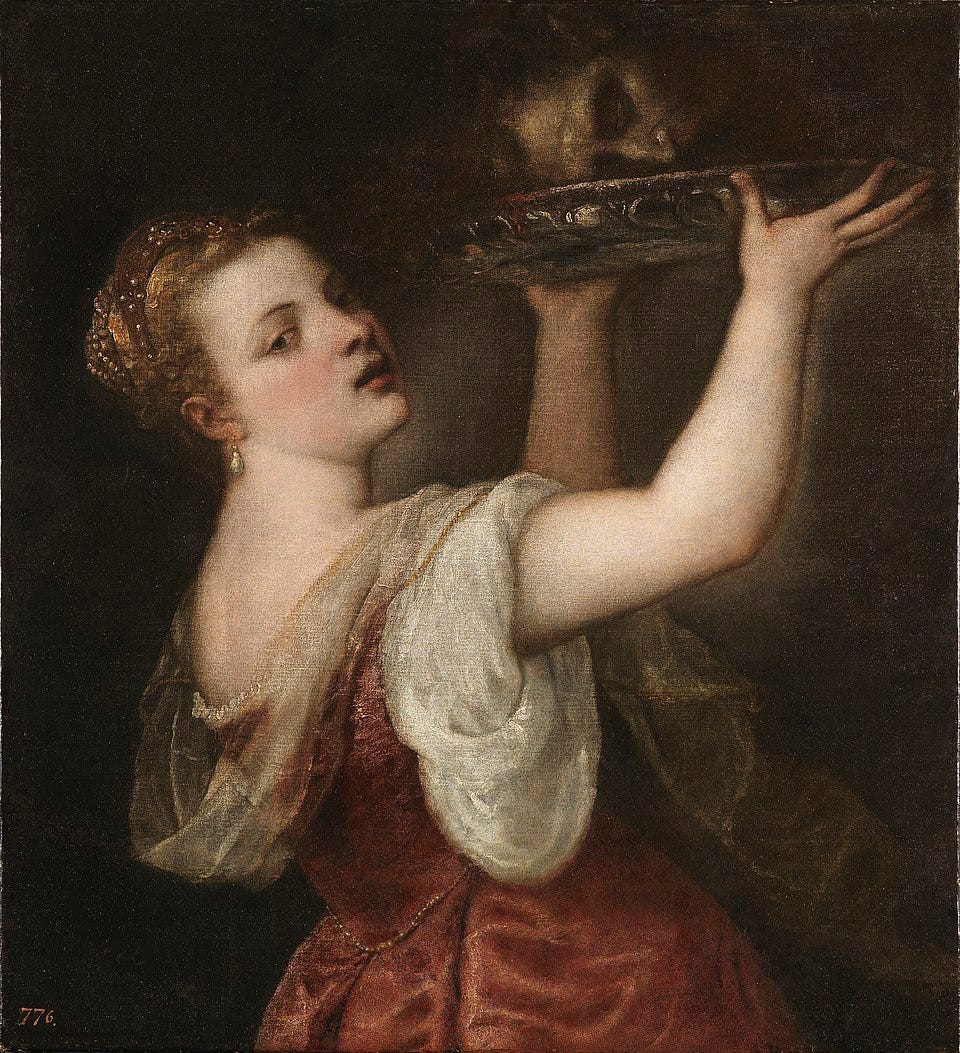

Medieval manuscripts and early Renaissance panels approached Salome with a kind of horrified fascination, depicting her as an instrument of her mother Herodias’s revenge against John the Baptist. In these early works, artists often showed her as emotionally blank or cruelly satisfied, holding the Baptist’s head with disturbing casualness. The famous Beheading of St. John the Baptist scenes from illuminated manuscripts frequently position Salome at the moment of transaction, receiving the head as one might accept a gift, her face betraying no horror at the violence she has caused. What’s striking about these portrayals is how they strip her of interiority, making her a vessel for someone else’s hatred. Yet even in their simplicity, these images reveal an undercurrent of anxiety about young women’s capacity to be corrupted, to carry out acts of violence without apparent remorse. The artists seem less interested in understanding Salome than in using her as a warning, but in doing so they created an archetype that later artists would explode into far more complex psychological territory.

From Seductress to Symbol

The late nineteenth century witnessed Salome’s reconstruction from biblical cautionary tale into the era’s most potent symbol of dangerous femininity. Symbolist painters like Gustave Moreau obsessively returned to her image, covering her with jewels and placing her in hallucinatory spaces that seemed to exist outside time. These artists were responding to an intense cultural disorder as women began demanding education, property rights, and political participation. Salome became a screen onto which society projected its terror of the New Woman, that emerging figure who refused traditional feminine passivity. In Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations, she appears mystic, her sexuality not inviting but simply just cold. Franz von Stuck painted her dozens of times, each version more explicitly sexual than the last, her body covered in transparent fabrics as she holds the Baptist’s head. These were attempts to contain the threat of female autonomy by reworking it into aesthetic object. The Decadent movement embraced Salome precisely because she represented everything bourgeois society claimed to fear: uncontrolled female desire, the mixing of sacred and profane, beauty intertwined with death.

Oscar Wilde’s 1891 play “Salome” and Richard Strauss’s 1905 opera based on it fundamentally altered her story by giving her an interior life and authentic desire. Wilde made the shocking choice to have Salome genuinely lust after John the Baptist, requesting his head not from obedience to her mother but from sexual frustration after he rejects her advances. She kisses his severed head in the play’s climax, declaring her love. This was revolutionary because it granted Salome agency over her own narrative, making her the subject rather than the object of desire. Strauss’s opera pushed even further, using dissonant, chromatic music to express Salome’s psychological unraveling and sexual awakening. The final scene, where she performs a monologue to the dead prophet’s head, gave opera audiences something they had never encountered: a teenage girl expressing unashamed sexual desire and rage at rejection. Both works caused immediate scandal, with Strauss’s opera banned in several cities, but they also opened new artistic possibilities.

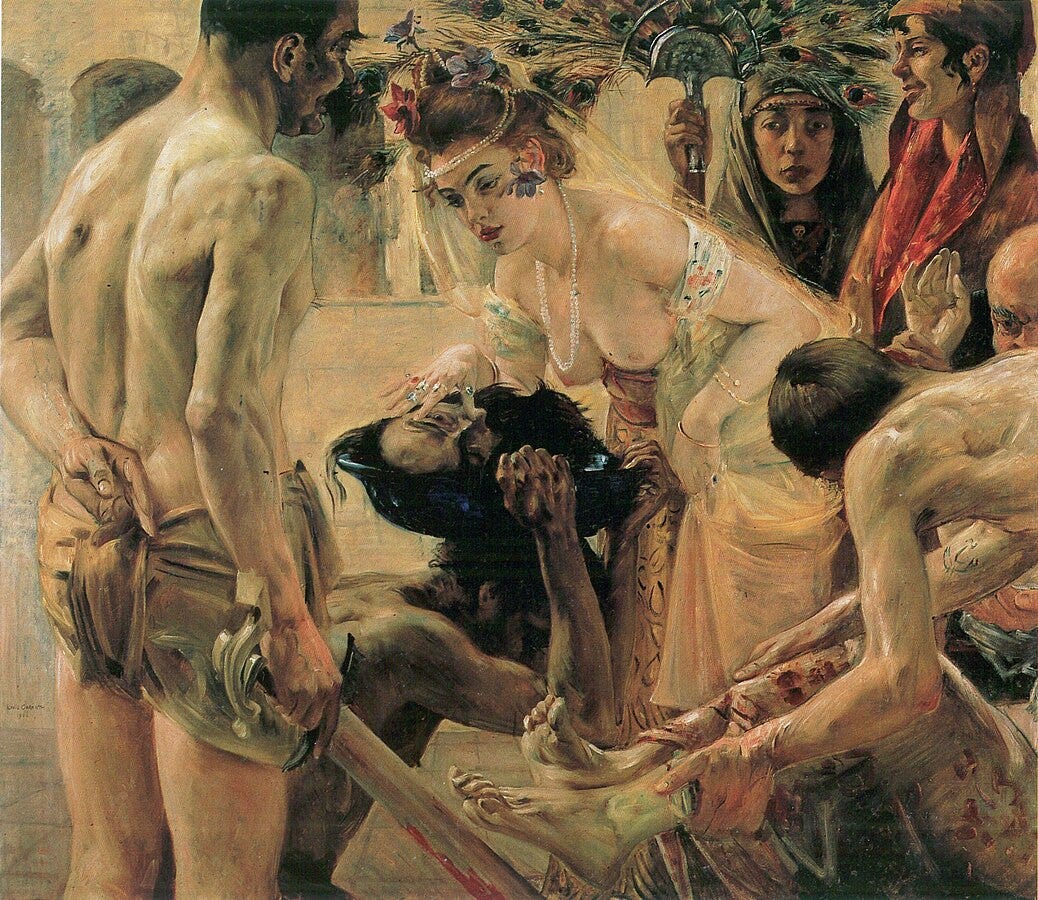

What becomes unavoidable when studying Salome’s artistic history is how thoroughly male artists used her to work through their own psychological tangles about women and sexuality. Nearly every major Salome painting was created by a man, and nearly all focus obsessively on her body, her dance, her capacity to seduce and destroy. These artists claimed to be depicting female danger, but they were really documenting their own ambivalence about desire. When Lovis Corinth painted Salome, she appears drugged or entranced, barely conscious of her own actions, suggesting that female sexuality itself is a kind of madness. When Moreau painted her, she becomes almost alien, covered in so many jewels and patterns that she barely seems human, as if extreme beauty necessarily dehumanizes. These men were trying to understand something about women that frightened them, but they could only approach it through fantasy and projection. The dozens of Salome images they created tell us less about actual women than about the psychic burden men carried in imagining female power. They needed Salome to be monstrous because the alternative was acknowledging that women were people with desires and wills of their own, a recognition that would have shattered the entire structure of how they understood gender, art, and their own identities.

If exploring how Salome became a mirror for society's anxieties about women, power, and violence was worth your time, please help keep it freely available to others. Support independent art criticism so we can all keep questioning what we see in museums and what those images reveal about ourselves.

Thank you very much!

This was an awesome post.

I just wanted to point out however that you (and anyone who isn’t invested in hermetic related inquiry) missed an important detail about Salome’s dance that has nothing to do with sexuality.

“Dancing the Seven Veils” This is esoterically important. The 7 veils alludes to the seven Spheres or planets in the “chain of manifestation.” There is meant to be some significance to spirit descending or assent through the celestial realms.

I am actually not sure how to interpret this in the context of Salome’s request for John the Baptist’s head. Perhaps it was Envy that she could not ascend the heaves and in spite had John killed -an adept holy man. And why she kissed his severed head in a moment of remorse or admiration??