Rome's Most Macabre Trial

The Cadaver Synod of 897

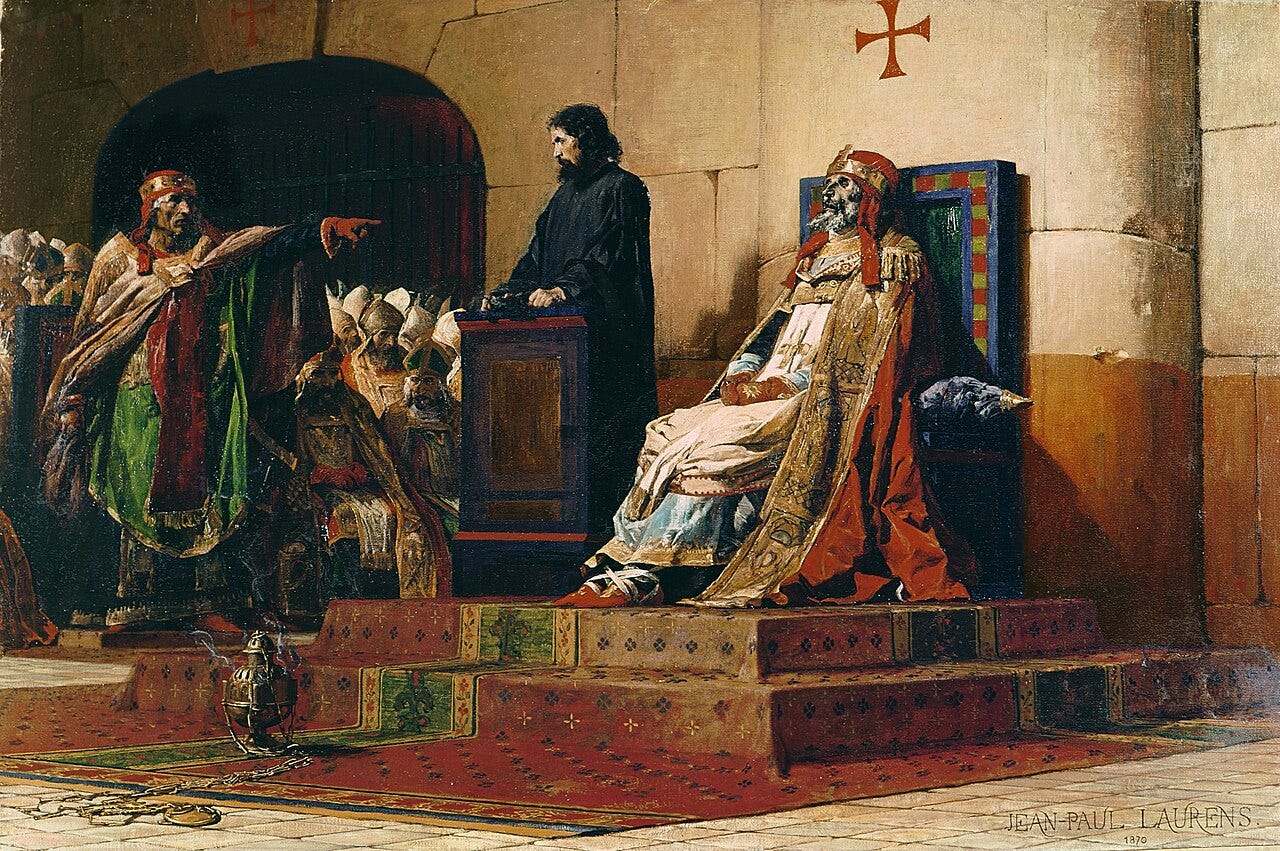

Picture this: January 897, inside the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome. Cardinals and bishops fill the chamber in their ceremonial robes. At the center sits a defendant on the papal throne, but he’s been dead for nine months. Pope Formosus’s corpse, dressed in full papal vestments, was exhumed from his tomb and propped upright to face charges of perjury, illegally ascending to the papacy, and violating church law by holding multiple bishoprics. A terrified teenage deacon stood beside the decomposing body, defending it while Pope Stephen VI screamed accusations and hurled insults at the rotting remains. This was the Cadaver Synod, one of the most grotesque spectacles in papal history, revealing the violent chaos consuming the Catholic Church in the ninth century.

A Posthumous Vendetta

Formosus was born around 816 in Rome and rose through church ranks to become cardinal bishop of Porto in 864. Pope Nicholas I sent him on missions to Bulgaria and France, where he demonstrated both religious and diplomatic skills. His talent made him a papal favorite, but it also made him dangerous. In 876, Pope John VIII accused Formosus of corrupting Bulgarian minds, conspiring to usurp the papacy, and deserting his diocese without permission, leading to his excommunication. After John VIII’s death in 882, Pope Marinus I restored Formosus to his position at Porto, and by 891, he was unanimously elected pope. His papacy threw him into brutal power struggles with the Holy Roman Empire’s nobility. Formosus crowned Lambert of Spoleto co-emperor in 892, but grew nervous about the Spoleto family’s aggression and invited Carolingian king Arnulf of Carinthia to invade Italy in 893. When that failed, Formosus renewed his invitation in 895, and Arnulf crossed the Alps, entering Rome where Formosus crowned him Holy Roman Emperor in early 896. Formosus died in April 896, leaving Rome in chaos.

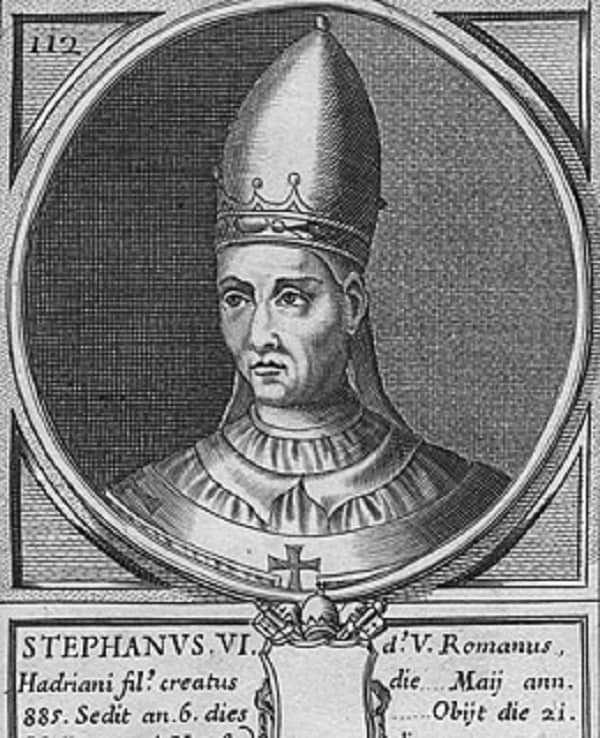

Stephen VI was a native Roman and member of the Spoleto family who had been consecrated bishop of Anagni by Formosus, possibly against his will. When Boniface VI died after just two weeks as pope, Stephen was elected with the backing of Lambert of Spoleto and his mother Agiltrude, giving the Spoletan faction control of Rome. Stephen’s alignment with the Spoleto faction positioned him as their tool for revenge against Formosus, who had betrayed them by crowning their rival Arnulf as emperor. In early 897, Lambert traveled to Rome to be formally re-crowned as emperor and convinced Stephen to hold the Cadaver Synod. The true purpose of the trial was political vengeance, as the Spoletans charged that Formosus had crowned an illegitimate descendant of Charlemagne after already crowning Lambert. Stephen had developed an intense hatred for Formosus, seeing the trial as a way to display loyalty to Lambert while destroying his predecessor’s reputation and preventing him from becoming a saint by having his body destroyed. The spectacle was calculated cruelty wrapped in legal theater.

The stakes were everything. By the time of Formosus, the ability to anoint emperors had become a curse more than a blessing, plunging popes into high-stakes games of intrigue with monarchs jostling for dominance. Whoever controlled the papacy could appoint favorable bishops and abbots, crown emperors, and wield immense religious legitimacy across Christendom. Between 872 and 965, around thirty men served as popes, and between 896 and 904, a new pope was elected almost every year as Roman aristocratic families battled for control. Stephen’s annulment of Formosus’s pontificate freed him from charges of irregularity in transferring from Anagni to Rome, since Formosus had appointed him bishop there. By destroying Formosus, Stephen erased the legitimacy problem of his own rise while satisfying his Spoletan masters. The Cadaver Synod was ultimately about rewriting history itself, proving that in ninth-century Rome, the victors didn’t just write the story, they literally dug up their enemies and forced them to confess their crimes before an audience of the living.

A Grotesque Spectacle

In January 897, Pope Stephen VI ordered the tomb of Formosus opened and his nine-month-old corpse exhumed, dressed in full papal vestments, and seated on a throne in the Basilica of St. John Lateran. The decaying body was propped up like a broken puppet while Pope Stephen acted as prosecutor and a young deacon was given the impossible responsibility of defending the decomposing remains. During the trial, an earthquake rocked Rome, which many took as a sign of displeasure from God, but the proceedings continued. According to chronicler Liutprand of Cremona, Stephen shouted at his dead predecessor, demanding answers to charges and asking “When you were bishop of Porto, why did you usurp the universal Roman See in such a spirit of ambition?” The audience watched in stunned horror as Stephen screamed accusations at rotting flesh that could offer no defense.

Stephen accused Formosus of perjury, of illegally ascending to the papacy, and of illegally presiding over more than one diocese simultaneously. The charges were also based on Formosus supposedly breaking an oath to remain a layman and lying under oath about his intentions toward church office. These accusations were a repetition of the charges Pope John VIII had leveled against Formosus decades earlier when he was excommunicated for deserting his diocese and aspiring to become Archbishop of Bulgaria. The list of accusations was used to attack Formosus for political reasons rather than to clarify legal matters, and the outcome was already decided before the trial began. The synod declared all of Formosus’s acts as pope null and void, erasing his papacy retroactively and declaring every ordination he performed invalid. This sent shockwaves through the Church because many active clergy owed their positions to Formosus.

After being found guilty, Formosus’s corpse was stripped of its papal vestments and the three fingers from his right hand that he used in blessings and consecrations were hacked off. The body was then dressed in common clothes and buried in a pauper’s grave. Not content with this humiliation, Stephen ordered the body exhumed again and thrown into the Tiber River to prevent any possibility of burial in holy ground. According to legend, fishermen later pulled the waterlogged corpse from the river, and rumors spread that the decomposed body was performing miracles. Modern historians suggest Stephen may have been trying to prevent Formosus from becoming a saint by destroying both his memory through damnatio memoriae and his physical remains so no cult could form around relics or a tomb. The calculated brutality backfired spectacularly. Public opinion in Rome turned violently against Stephen, riots erupted, and within months he was deposed, imprisoned, and strangled to death. The dead had their revenge after all.

The Synod’s Legacy

The Cadaver Synod became a symbol of ecclesiastical madness and a low point for the papacy, known as the beginning of the “Saeculum Obscurum” or “Dark Age of the Papacy,” a period when the Roman Church became corrupt, violent, and dominated by secular forces. The calculated effort to destroy both Formosus’s memory and physical remains shows the deeper anxieties of a Church caught in political upheaval. By trying Formosus posthumously, Stephen VI was attempting to erase a political rival’s legacy and reassert his faction’s control over Church law and imperial authority. The Cadaver Synod stands as the ultimate cautionary tale about what happens when religious institutions become fully corrupted by political ambition. It revealed a papacy so consumed by factional warfare that it lost all moral authority, reducing the vicar of Christ to just another warlord willing to defile the dead for temporary political advantage. The Church tried to bury this shameful episode, but it remains as proof that sacred institutions can descend into barbarism when power becomes their only priority.

By becoming a supporter, you join a dedicated community committed to preserving and sharing important historical narratives that might otherwise remain obscure or inaccessible. Your contribution ensures that researched content like this continues to be freely available while supporting the ongoing mission to make history engaging and comprehensible.