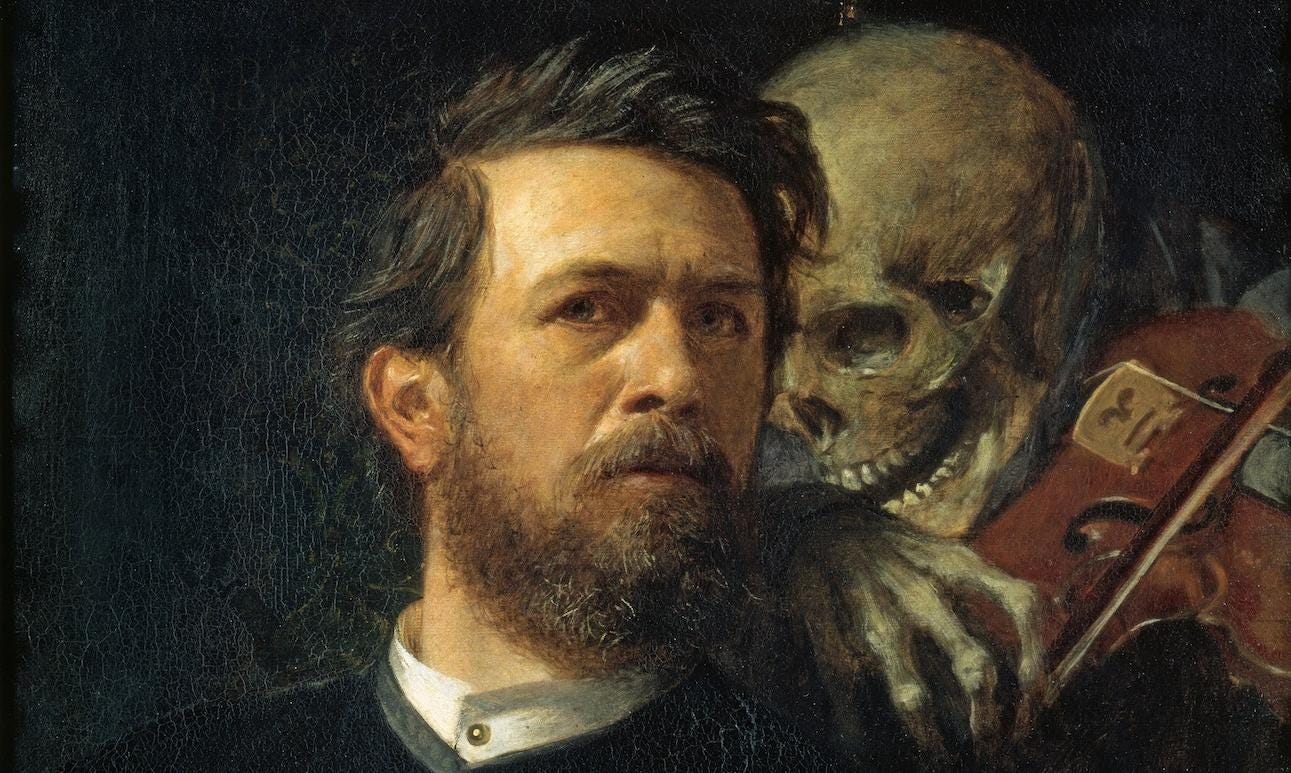

Is Death a Misfortune?

Why We Don't Fear the Past But Tremble at the Future

We all carry this question with us, often in the corners of our minds. It surfaces not as a dry, philosophical puzzle, but as a feeling, a cold stillness that can settle in the chest during a moment of loss, or in the moment of a sleepless night. It is the question of whether death, our one true certainty, is a terrible misfortune. This wondering is a profoundly universal part of being human. It stirs a logical curiosity about what death is, tangled together with a deep and wordless unease about what it means.

We are not looking for a simple answer, because perhaps no single answer exists that can satisfy every heart. Instead, we can turn to the wisdom of those who have walked this path of questioning before us, from ancient thinkers who sought tranquility to modern philosophers who dissected the nature of loss itself. This journey is not about discovering one final truth that will erase all doubt. It is about learning how to live with the question itself. It is about finding a way to hold the reality of our own ending in a way that does not paralyze us, but instead makes our living feel more honest, and more meaningful.

The Epicurean Comfort: Why Death Is “Nothing to Us”

The ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus (341–270 B.C.E.) offered a radical argument for why the fear of death is irrational. His main thesis, as timeless as it is startling, is this: “Death does not concern us, because as long as we exist, death is not here. And once it does come, we no longer exist.”

To understand this, imagine a period of dreamless sleep. When you are unconscious, you do not experience the passage of time; you simply jump to your next conscious moment. Epicurus argues that death is like this, but permanent. The state of being dead has no experience at all: no silence, no darkness, no time because the conscious self required to experience anything has ceased to be. The reason we struggle to imagine this state is that consciousness is all we have ever known; its absence feels like an outrageous impossibility.

His follower, the Roman philosopher Lucretius, added a powerful symmetry to this argument. He pointed out that we do not feel any distress about the vast stretch of time before we were born. That period of non-existence was “as naught to us.” Lucretius argued that the state of non-existence after death is identical. If we do not fear the one, he reasoned, why should we fear the other?

For Epicurus, the real evil is not death itself, but the fear of death, which causes anxiety and ruins our pleasure in living. By realizing that death itself is nothing to be experienced, we can achieve ataraxia; a state of tranquil imperturbability and freedom from fear.

The Modern Objection: Death as a Deprivation

For many of us, the Epicurean argument, while logically compelling, feels emotionally incomplete. This is where the modern philosopher Thomas Nagel and his “deprivation account” of death’s evil present a powerful counter-argument. This view concedes that death is not a bad experience but argues that it is bad for the person who dies because it deprives them of the good things they would have otherwise enjoyed.

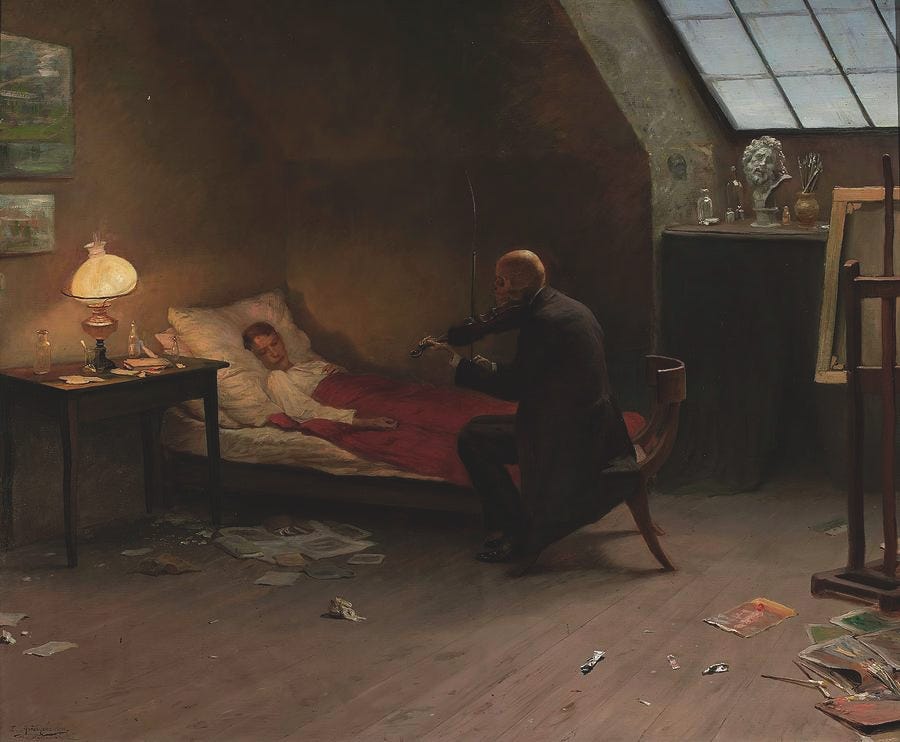

When a young person dies in an accident, our intuition screams that a tragedy has occurred. The tragedy is not the experience of being dead, but the loss of a future that contained potential happiness, love, and achievement. Nagel’s view is that death is a misfortune because it abruptly cancels the valuable life that would have continued. From this perspective, death is an evil not because of what it is, but because of what it takes away.

The Puzzling Asymmetry: Why We Fear the Future, Not the Past

This brings us to the heart of a deeply human puzzle: Why does the deprivation of future goods seem so terrible, while the deprivation of past goods (the time before we were born) seems meaningless? If Lucretius is right about the symmetry, why don’t we feel it?

Some philosophers argue the difference is not irrational but rooted in the structure of our lives and our identities. Our “thick personhood”—the unique tapestry of memories, relationships, and projects that makes us who we are—unfolds in one direction: forward.

The Impossibility of an Earlier Birth: It may be logically possible for the human organism that is you to have been born earlier. However, the specific person you are, the one with your particular biography, who met your specific spouse, and holds your unique memories, could not have existed earlier. Your wife, for instance, did not exist 100 years ago, so you could not have met her then. Therefore, you are not deprived of a life you could have had before you were born, because that life was impossible for you as the person you are.

The Possibility of a Later Death: In contrast, it is clearly possible for you to live longer than you will. Your biography could be extended into the future without contradicting the facts of your identity. You could have continued your relationships, finished your projects, and experienced more of life’s joys. Therefore, death deprives you of a future that was genuinely possible for you.

This explains the asymmetry: we fret about missing our future because it was a real part of our possible life story, while we don’t panic about the past because it never belonged to us in the first place.

Would We Live the Same? Mortality and the Meaning of Life

A common cultural argument is that death is what gives life meaning. The idea is that if we were immortal, life would become boring, stagnant, and ultimately meaningless. We see this theme in myths like that of Tithonus, who was granted immortality but not eternal youth, and was left to age miserably forever.

However, proponents of the deprivation account like Nagel would challenge this. If life is intrinsically valuable, then more of a good thing is better. From this perspective, an immortal life would not necessarily be meaningless, provided it continued to contain valuable experiences and projects.

The deeper, more personal question is whether the certainty of death shapes how we live. The Epicurean would say that accepting death removes anxiety and allows us to fully savor present pleasures. The Nagelian might argue that the knowledge of our limited time creates a precious urgency, compelling us to choose our projects wisely and love more deeply because our opportunities are finite. In this view, death doesn’t create meaning, but it can fuel it.

A Heartfelt Call to Reflection

The debate between Epicurus and Nagel may never be fully settled, as it touches on our most fundamental values about time, identity, and the good life. Rather than seeking a final answer, perhaps the goal is to use this philosophical tension as a tool for reflection, allowing it to shape a more attentive and purposeful existence.

If you find Epicurus persuasive, practice his wisdom. When anxiety about mortality arises, remind yourself that the state of death itself is not an experience you will ever have. Use this to release fear and focus on cultivating pleasure and tranquility in your present life.

If you find Nagel more compelling, let his argument reinforce the immense value of your finite time. Let the knowledge that death is a deprivation motivate you to cherish your relationships, pursue meaningful projects, and fully appreciate the goods of your existence.

Whichever path resonates, the ultimate conclusion is the same: to live a life, whether finite or not, that is rich in value, connection, and mindful appreciation. By confronting the reality of death with both reason and heart, we do not simply answer a philosophical question, we learn how to live.