Cutting for Beauty

Inside the Medici Family's Underground Anatomy Empire

The Medici family built their legacy on marble and canvas, filling Florence with monuments that still draw millions of visitors each year. But beneath the gilded surfaces of their patronage lay a peculiar enterprise that would have shocked the very citizens who admired their commissioned works. While Cosimo and Lorenzo de’ Medici publicly championed divine proportion and classical ideals, they secretly funded something far more transgressive. In the dim workshops hidden behind respectable facades, artists under Medici protection were dissecting human corpses, peeling back skin and muscle to understand what made beauty possible. The family understood that you couldn’t paint the human form convincingly without knowing what lurked beneath it.

Fifteenth-century Florence existed in a strange state of contradiction. The city worshipped antiquity while the Church still held enormous power over daily life. Desecrating the dead remained a mortal sin, punishable by excommunication or worse. Yet Florence was also becoming Europe’s intellectual engine, a place where asking questions mattered more than accepting doctrine. The Medici banking empire had made the family wealthy enough to create their own rules, and they recognized that scientific knowledge could be as valuable as gold. When their sponsored artists began requesting access to bodies from hospitals and prisons, the Medici didn’t flinch. They saw an investment opportunity where others saw only taboo.

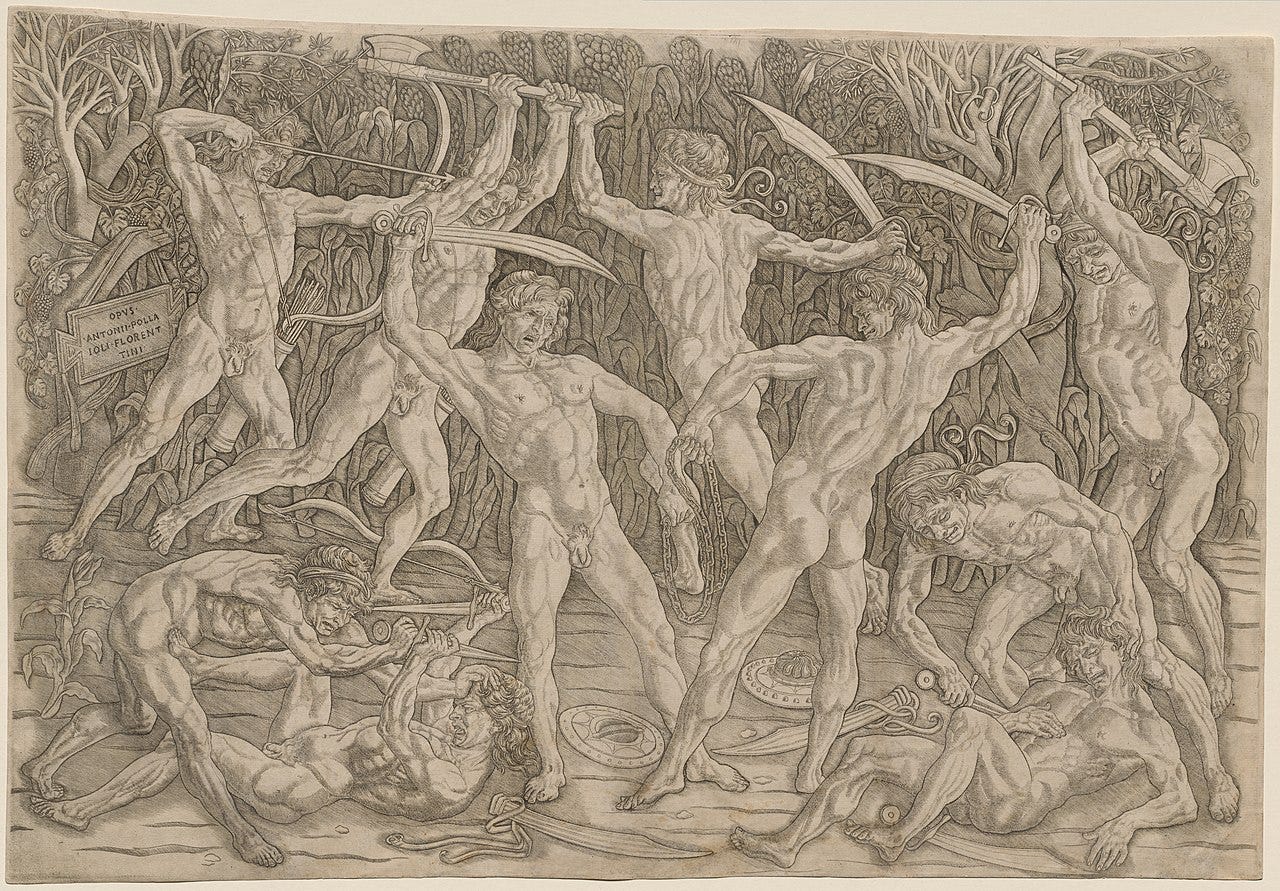

What emerged from these clandestine dissections completely changed Western art forever. Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s engravings of battling nudes revealed musculature that no amount of observation of living models could have taught him. Andrea del Verrocchio’s sculptures displayed an anatomical precision that came directly from his time with scalpel in hand. Even the young Leonardo da Vinci, working in Verrocchio’s Medici-funded workshop, began his lifelong obsession with human anatomy in these years. The family’s willingness to shelter this forbidden research meant that Florentine art achieved a realism that left other European centers scrambling to catch up.

The Renaissance Paradox

Lorenzo de’ Medici maintained relationships with hospital administrators and prison wardens specifically to secure fresh corpses for his circle of artists and physicians. When someone died unclaimed at Santa Maria Nuova hospital, an arrangement ensured the body found its way to approved workshops before dawn. The family even funded the construction of specialized rooms with stone tables and drainage systems, spaces designed exclusively for dissection. The Medici treated human anatomy as a resource to be harvested and studied systematically, applying the same organizational genius they used to run their banking empire.

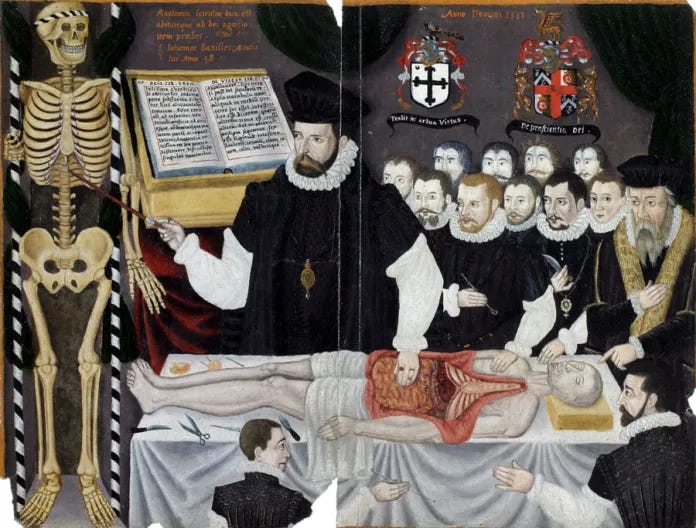

By the 1480s, the Medici palazzo housed what amounted to among Florence’s first anatomical research center. Scholars, artists, and physicians gathered in private chambers to share findings from their dissections. Antonio Benivieni, a pioneering pathologist, performed some of the earliest recorded autopsies under Medici protection, documenting his discoveries of gallstones and heart defects. Artists brought sketches of muscle groups and bone structures to compare notes with doctors who approached the same bodies from different angles. The family provided not just corpses but also the intellectual space for collaboration. They understood that art and medicine were asking the same fundamental question about how human bodies actually worked, and they bankrolled both pursuits without demanding immediate returns.

Fifteenth-century medicine still relied heavily on ancient Greek texts that had never been verified through direct observation. The Medici were gamblers by trade, and they bet that firsthand knowledge would eventually prove more valuable than inherited wisdom. Their artists needed to understand anatomy to paint convincing figures, but the family’s investment suggested they believed these studies might unlock something bigger. They were right. The detailed anatomical drawings and observations that emerged from Medici-funded workshops laid groundwork for modern medicine, even as they produced the masterpieces we still celebrate today.

Dissection and Artistic Revolution

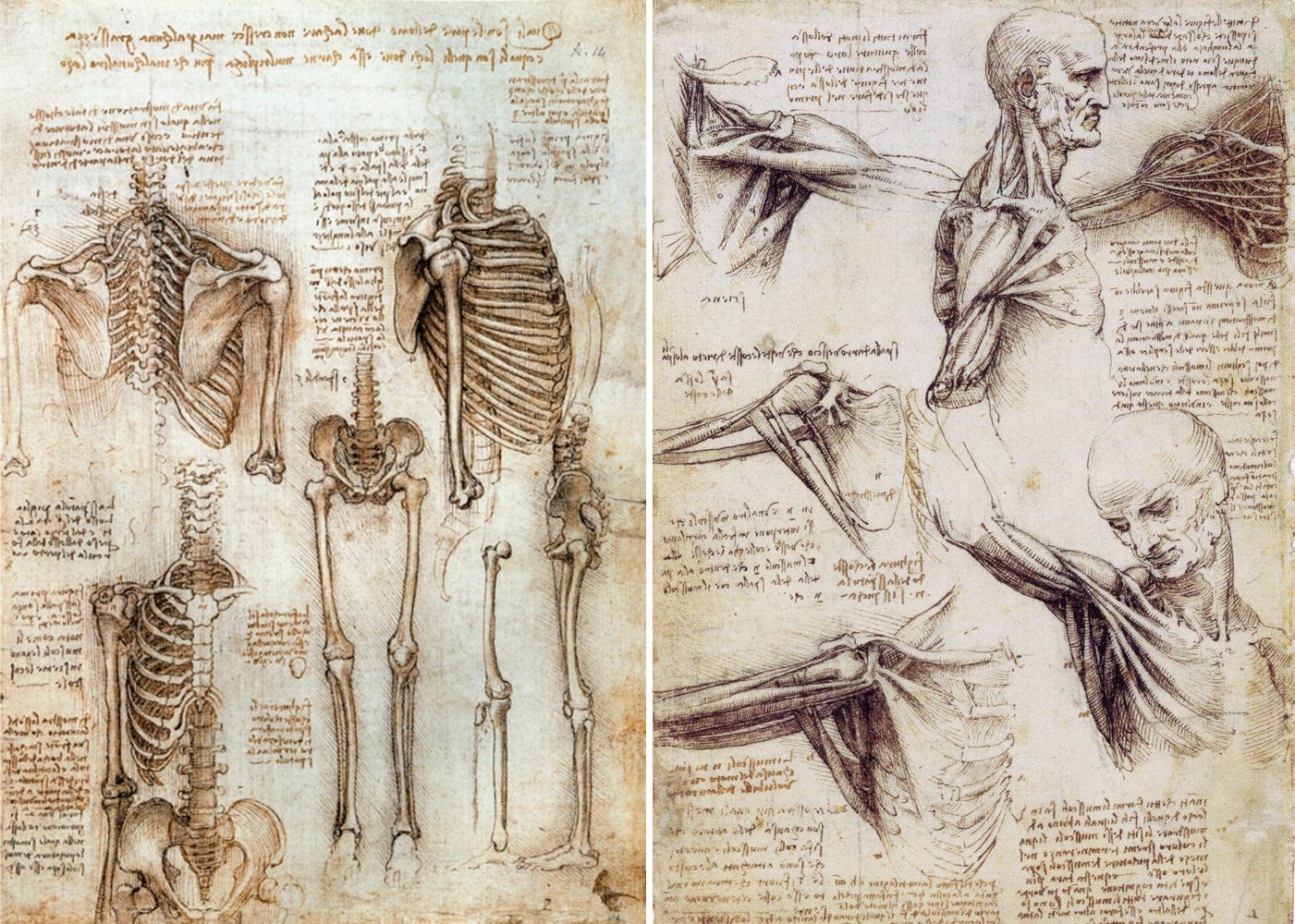

Leonardo da Vinci dissected at least thirty human corpses during his lifetime, and many of those early experiences happened in Florence under Medici protection. His notebooks reveal an obsession that went far beyond what any painter needed to know. He drew the chambers of the heart, traced nerve pathways through the spine, and documented the position of a fetus in the womb. Leonardo had access to bodies that most artists could only dream of examining, and the Medici network made it possible. When he needed a corpse, hospital contacts provided one. When church authorities grew suspicious, Medici influence kept investigations at bay. His anatomical drawings, celebrated today as masterworks of scientific illustration, began as the studies of a young artist who had powerful patrons willing to bend rules. Without that protection, Leonardo might have sketched muscles from the outside and guessed at what lay beneath like countless painters before him.

Michelangelo took a different path to the same forbidden knowledge. As a teenager living in the Medici household, he gained access to the corpses at Santo Spirito monastery through connections Lorenzo de’ Medici had arranged. He spent months dissecting bodies by candlelight, teaching himself how muscles attached to bone and how skin stretched over underlying structures. Michelangelo cut into flesh, pulled apart tissue, and memorized what he found. When he later sculpted David, every muscle in that marble body was exactly where it should, tensed precisely as it would be in a living person shifting weight onto one leg. The Sistine Chapel ceiling displays hundreds of figures, and each one shows a command of human anatomy that only came from seeing bodies opened and examined. Michelangelo’s art feels alive because he knew what made living bodies work, knowledge gained through acts that could have landed him in serious trouble without Medici backing.

The changes these studies created rippled through all of Renaissance art. Before widespread anatomical study, painted figures looked stiff and unconvincing. Artists relied on conventions and formulas, covering fabric over bodies they didn’t truly understand. After Leonardo and Michelangelo, that changed permanently. Suddenly paintings showed people in motion, with weight and balance and muscles flexing correctly beneath skin. Religious art became more powerful because Christ’s suffering on the cross looked real. The revolution wasn’t about style or technique in the traditional sense. It was about knowledge, hard-won and forbidden, that allowed artists to depict human beings as they actually existed. The Medici funded that knowledge, and Western art never looked the same again.

If you found value in learning what the Medici didn't want the public to know, help keep this work alive. Support independent writing so these stories remain free for anyone hungry to understand the real forces that shaped our world.

A small doll made of ivory to learn about the different organs. It can be seen during a visit to Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. Among the most distinguished alumni of the university are: Renaissance polymath Nicolaus Copernicus, Pope John Paul II and science fiction writer Stanisław Lem.

For some reason I knew this but never thought about it in the context of the theocracy. What a “turn a blind eye” situation for many involved.